THE TRIPTYCH – KAUSTINEN

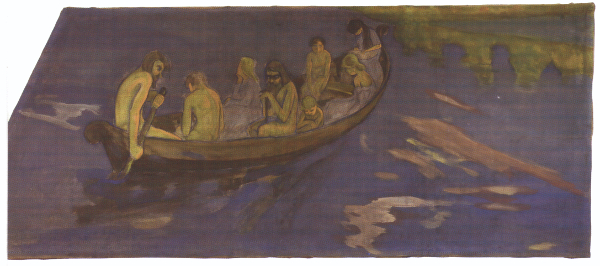

One part of the triptych

Restorer Marja Korhonen

In the summer of 1909, the town of Kaustinen completed its brand new youth association building. Built by the townspeople, it rose proudly on a hill in the center of the town, close to the local school. As Ilmari Wirkkala was known for his artistic skills, he was asked to create a painting that would both fit in with the youth association spirit and decorate the stage in the main hall.

The Finnish national epic Kalevala and particularly the famous works of artist Axel Gallen-Kallela, the “Aino” triptych and the painting “The Fratricide”, had made an impression on Wirkkala. Inspired by them, he began the work and the end result ended up being widely celebrated.

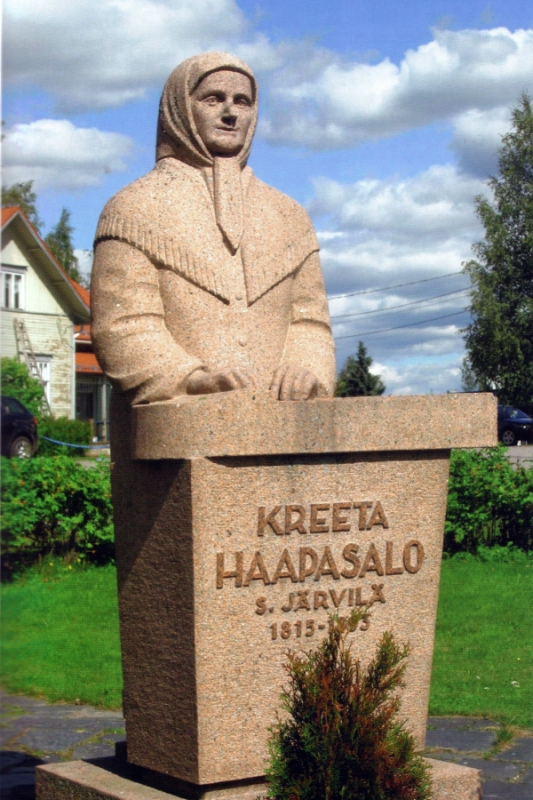

So Kreeta Haapasalo did get a statue in her honor, but it was a whole eight years later when the locals had finally managed to raise enough funds to erect it. On a hot summer's day, 4th July 1954, the statue designed by Ilmari Wirkkala and made by his son Tauno was finally revealed. A businessman from Kaustinen named Sulo Peltoniemi had acquired a copy of the biography of Kreeta written by Lilli Lilius which was gifted to the local heritage association on behalf of the Regional Council of Ostrobothnia.

Ilmari Wirkkala had made a lot of friends in Veteli and this led to some of his first larger projects being commissioned in the neighboring town.Ilmari Wirkkala had engaged in research to uncover the life of Kreeta Haapasalo and this naturally led to him giving a speech at a gathering on 13th January 1946. He gave the crowd a detailed presentation largely based on recollections of people who had lived in the villages of Virkkala and Järvelä.Ilmari’s son Tapio Wirkkala graduated from University of Art and Design Helsinki in 1936. Ilmari supported his son in the beginning of his career and, for instance, facilitated him being commissioned to create a statue of a parliamentarian from Veteli, Juho Torppa. The father and the son traveled to Hattula to meet with Mr Torppa, and the end result pleased both the artists and the model himself, who said as much in a letter to Ilmari's relative Heikki Tunkkari. The head made of alabaster is on display at the local heritage museum in Veteli.

THE MONUMENT FOR THE KUORIKOSKIS, THE CHURCH BUILDER FAMILY – KAUSTINEN

The Youth Association paper called Pyrkijä, commenting on the finished triptych soon after the inauguration on 5th September 1909, states that “[T]hose who have visited the Kaustinen youth association’s new home uniformly call it beautiful. The paintings by Ilmari Wirkkala decorating the walls are said to offer true artistic pleasure.“

The commentary continues: ”On the left, we see a long painting depicting a maiden carrying a lit torch. There are three paintings above the stage opening. The first is the most impressive, symbolic depiction of the Tuonela river that separates the living from the dead in the Finnish mythology. A group of people sit in a boat, quietly gliding on the water towards the other side. In the central canvas, as if a headline to the story, is a small square painting depicting a slender standing woman, her hand on a book and her serious eyes cast down, wistfully, at the book. Let us call the painting “The Oath”, for that is what its subject seems to suggest.

Lastly, on the right hand side of this small painting, there is a larger one, a figure of a snorting horse driven by a bearded plowman (the subject matter presumably derives from the national epic Kalevala).

There is another larger painting on the right hand side of the stage. Its subject echoes a Germanic heroic story. A slender maiden, shadowing her eyes from the sun with her hand, stands on top of a tower and peers into the distance. At the bottom of the tower, in turn, an armored knight with a spear in his hand sits on his proud horse, as if keeping guard.

The paintings by Mr Wirkkala suggest that he has been significantly influenced by Axel Gallen-Kallela – indeed, his overall style seems to be derived from that of his. Especially the smaller-size "The Oath" brings to mind the artist's impressive work ”The Fratricide”.

Similarly, when looking at many other paintings by Mr Wirkkala, it becomes clear that he seems to think very highly of the great Finnish artist, though this must not be interpreted as being detrimental to Wirkkala’s work. Quite the contrary.” (Pyrkijä, no. 13, 1909)

The Youth Association in Kaustinen donated the triptych to the local heritage association. The association recorded the works under the following names: 1) Crossing the Tuonela River, 2) A Blonde Girl in Blue and 3) The Beginning of Agriculture. The paintings on the sides of the stage were damaged over time and did not survive.

The triptych was eventually removed when the old youth association house gave way to a building dedicated to local musicians (in Finnish: Pelimannitalo, folk musicians’ house) that was relocated to the spot in 1973. The triptych suffered somewhat during the years it was tucked away, but in 2015 the Virkkala Tradition Association began the conservation work on it, ultimately finishing it in 2016.

THE LOCAL HERITAGE MUSEUM IN VETELI – VETELI

In 1930 Ilmari Wirkkala was 40 years old. Even though cemetery planning was taking up more and more of his time, he still continued to work for the benefit of this home region, and on an ever-increasing scale. Indeed, his first project in architecture was designing the local heritage museum for the town of Veteli. The building's shapes follow the lead of another building in the town, the so-called ‘long church’. The inauguration of the museum was on 10th July 1932.

The local heritage association had already been engaging in activities similar to those usually carried out by museums since 1912. The museum itself was erected by volunteers from the town. Its ground floor is dominated by a traditional, provincial main room consisting of kitchen facilities and a simply decorated sitting room with an old grandfather clock. For Ilmari Wirkkala, this setting was pleasant and he had cherished the peasant life in his writings already for a long time.

The museum displays, for instance, an alabaster portrait of assemblyman Juho Torppa from Veteli, made by Ilmari’s young son Tapio Wirkkala in the early 1930s.

“CHRIST IN THE WILDERNESS” AND CHURCH TEXTILES – PERHO

In the late 1930s, Ilmari Wirkkala engaged in frequent activities around Central Ostrobothnia. After completing the plans for the local heritage museum in Veteli, he was asked to design a cemetery for the neighboring parish in the town of Perho. In addition to this, he was also asked to paint the altarpiece for the church in Perho in 1938. Until then, the church built in 1903 did not have an altarpiece in the first place.

Ilmari Wirkkala chose the resurrected Christ as the topic for the altarpiece and the parish requested three different sketches. The first one was to depict Jesus wearing a crown of thorns and with a purple cape on his shoulders. The second sketch was to show the face of the Lord with raging masses of people behind him. The third topic was requested under the title of “Christ in the Wilderness”. They wished for a stylized piece that was “freely adapted to modern times”. They requested also that the wilderness in the piece was the wilderness found in Perho. In the foreground, the request stated, was to be Christ who points at his wounds and thus invites people towards salvation.

The church assembly were partial to options one and three. The six-member commission ended up voting for the latter sketch, and the completed “Christ in the Wilderness” was eventually revealed on 25th September 1938. The sermon that day highlighted the message conveyed by the painting.

Wirkkala’s work has been described as particularly engaging. The image communicates to the viewer that the Savior’s virtuousness is ever present in Perho. “To testify for this, familiar scenes of local nature have been captured in the altarpiece,” the parish rector wrote at the time. Those accustomed to ambling in the local wilderness will recognize some of the depictions of nature in the picture, such as the Esker of Salmela (Salmelanharju), on top of which a magnificent view onto the lake Syrjäjärvi opens up.

The cross symbolizing suffering appears in the painting in the form of a dried-up pine tree. This tree has also been seen as a representation of an actual unusual-looking pine tree in the lake Salamajärvi area. Some have pointed out the break from realism in the painting: in the background one can see a fjord, which contradicts the actual flatness of the landscape in western Finland. The bishop of Oulu, Samuel Salmi, however, saw in this that the painting represents the entire diocese: standing at its southernmost border, Christ welcomes the viewer to the diocese. In the background, in turn, one can see the northern fjords and thus the other extreme border of the area.

The work done for the church in Perho was an igniting spark for the Wirkkala family business. In 1936, the Perho parish requested Ilmari Wirkkala to design the textiles for the church as well. Thus his wife Selma Wirkkala had a chance to show off her craft skills and this resulted in several further orders for the couple. Church textiles made by Selma Wirkkala were also sold to several churches in the capital area.

Later on Ilmari Wirkkala was tasked with designing a monument for the church builder family of the Kuorikoskis, to be erected next to the church in Kaustinen. This beautiful monument was revealed in the summer of 1939.

The monument is 4.5 meters tall and made out of granite. It is shaped like a bell tower and holds a large iron cross at the top. At the bottom of the cross a piece of text wraps itself around the base: ”To the memory of the church builder Kuorikoskis”. On three sides of the monument, plaques commemorating the four Kuorikoski generations include the years of their birth and death and the number of churches and bell towers each of them built. The fourth plaque comes with a text: ”O, Lord's holy temple, blessed is your gate. You are dear to us.”

The monument was revealed on 6th July 1939. A collection had been set up to fund it, and half of the 21,000 marks needed had been raised by this time. One of the speakers at the event, Lyydia Järvelä, told the audience that the thought of erecting a monument to the family had occurred to her already 21 years earlier when the last church builder of the family, Jaakko Rauma-Kuorikoski, was laid to rest.

For Ilmari Wirkkala the project was particularly important in that his lineage on his mother’s side connected with the Kuorikoski family. Indeed, he was also one of the speakers at the gathering along with Minister of Agriculture Viljami Kalliokoski and the Rector of Kaustinen, Harri Pirilä. Pirilä read the speech written by professor Heikki Klemetti who was unable to attend himself due to illness.

”THE RECLAIMER” STATUE AND THE MONUMENT FOR FALLEN SOLDIERS – VETELI

While Ilmari was hard at work creating the monument for the Kuorikoskis in Kaustinen, Tapio Wirkkala was working on “The Reclaimer” statue (Raivaajapatsas) set to be located in the town of Veteli. It is the first statue in all of Finland erected to commemorate the work done on reclamation grounds.

The bronze statue was one of the first interpretive works made by Tapio Wirkkala, and it is said that the artist later on noted this as well, with a hint of awkwardness: ”it is one of the works from my early years – and it shows”. The statue was revealed on 30th July 1939 with around 2,000 people in attendance.

The event coincided with the 300th anniversary of the parish in Veteli. The project was initiated by the local heritage association, but the effort required some combining of forces. The heaviest load at the time was carried by chairman Santeri Torppa and secretary Heikki Tunkkari. The plan had originally been hatched in an association meeting on the rocky hill of Puusaari in 1932.

A couple of years later Heikki Tunkkari presented to the association a sketch by Ilmari Wirkkala related to something else entirely. The sketch involved raising the triangle-shaped area of ground next to the bell tower slightly and putting seating there around a so-called story stone. This would make the old spot where men always gathered around to chat before Sunday sermons more peaceful and beautiful. The spot also came with a pleasant view towards the fields near the center of the Veteli municipality, on both sides of the river valley.

The following year saw the amalgamation of plans involving both the story stone and the statue. They decided to request a sketch for the statue from Tapio Wirkkala, with his father Ilmari also taking part in planning the future site for the artwork. The artists submitted their plan in February 1936. According to the notes from the association meeting at the time, they were very pleased with the plan.

The cost estimate was 20,000 Finnish marks. It was a large sum of money those days, and raising it seemed like a monumental task at first. Heikki Tunkkari grew somewhat frustrated at some of the comments he received at the time: ”[O]ne shouldn’t sacrifice funds for inanimate objects, they say, but only invest them in something productive.”

The project, however, ended up receiving significant financial support from a distinguished businessman S. A. Harima who covered the artist’s fee, the cost of the casting work and any costs associated with the base. In addition, the stainless steel manufacturer Outokumpu Oy gifted the copper, all 215 kilograms of it. Farmer Aleksi Kangas, in turn, donated the land: 1.5 hectares.

Lauri Pekola from Veteli put in perhaps more effort than most in manufacturing the statue’s base. Unfortunately this was because he had to redo his work after originally basing it on incorrect measurements, resulting in a platform that was too low. This first attempt was later on used in a grave monument of a notable clergy family of Raumannus, positioned next to the church.

After a special church service on 30th July 1939, a celebration was held near “The Reclaimer” statue. Ilmari Wirkkala read a poem written especially for the occasion by Sauramo Oksanen. His wife Selma Wirkkala was also one of the many invitees to the celebrations.

Tapio Wirkkala's work received due praise. Heikki Tunkkari, holder of the Finnish honorary title kunnallisneuvos, gave a speech at the occasion: ”Tapio Wirkkala has created a piece of art where beauty meets a noble intent rooted in an idea,” he said and continued to address the artist personally: ”You have made the cold metal speak a language that we here understand.”

People of Veteli have always thought that “The Reclaimer” statue is an appropriate and honorable tribute to the work of land reclaimers. Much later, however, in 1987, the government banned land reclamation. On the day the law came to effect, the townspeople noticed that the statue had been covered with a giant sack. They later discovered that the people behind the stunt had been some of the local young farmers who thought that the symbol of farming spirit should not be forced to witness the day of shame.

The monument for fallen soldiers located in the church grounds in Veteli was created by Tapio Wirkkala after the wars and it is more stylized than “The Reclaimer”. The impressive figure of a soldier in a snow suit made out of gray granite in 1947 fits right in its milieu. The Wirkkalas subsequently used the statue in their brochures, a clear statement of the artist himself being pleased with the work as well. The statue was ordered already in 1940, but due to the increasing war effort it got postponed. Eventually the warrior statue was joined by 104 memorial crosses made by Lauri Pekola. A special memorial service for fallen soldiers was held on 3rd August 1947.

When the Winter War broke out, Finland did not have any plans on how and where the fallen soldiers would be buried. Initially the popular view was that the deceased would be buried close to the battle locations, as it was usually done. It did not take long, however, for the churchmen and parishes operating on the Karelian Isthmus to suggest that the fallen should, if at all possible, be buried in their home towns.

The man behind the idea was a Veteli-born rector and rural dean Johannes Sillanpää who was the military chaplain at the Karelia Guard Regiment and the garrison at Vyborg during the Winter War. His actions were crucial in the early stages of the war. After a couple of weeks of confusion, the fallen soldiers began to be transferred to their home parishes.

The White Guard contended that they should have a central role in the process and on occasion this led to disagreements. During his career, Ilmari Wirkkala had grown highly knowledgeable regarding Finnish cemeteries and he would be consulted whenever White Guard representatives and parishes needed any advise. As he was already over 50 years of age at the time, he had been relieved of any duties at the front.

As it turned out, Wirkkala was a most suitable person to mitigate questions related to memorials to fallen soldiers. The practices surrounding the establishment of memorials were quickly standardized. In a leaflet published by an association called Friends of Cemeteries (Hautausmaiden Ystävät ry) in 1940, Ilmari Wirkkala discussed in great detail the principles related to the placement of monuments. His aim was to inform parishes, following his view that for parishes, memorials for fallen soldiers were both rather expensive investments and also closely tied to local history and tradition that needed to be nurtured and cared for. ”Parishes will be appreciated, thanked or disapproved by future generations based on what we do now with the graves and memorials of our fallen soldiers.” He also took the opportunity to remind his readers that when suggesting so-called ”artistic” statues to be placed on church grounds, one should keep to tasteful designs and at least nude statues would be out of the question. ”This is not about building monuments celebrating war, these are gravestones!”

THE STATUE OF KREETA HAAPASALO – KAUSTINEN

The Second World War and the Continuation War had barely come to an end when Ilmari Wirkkala was again back in his home town. It was during the Christmas holiday of 1945 when the townspeople of Kaustinen with particular interest in local heritage expressed their wish to erect a statue in honor of the town's most famous artist, folk singer Kreeta Haapasalo (1813-1893). (There is some doubt as to the year when Kreeta was born. According to some documents she was born in 1815, but she herself remembered having been born in 1814. The strongest evidence, however, seems to point towards the year 1813.)

Kreeta Haapasalo's marriage touched upon the Wirkkala family as well, and Ilmari Wirkkala wrote about it in 1946. While it would seem that he did not have access to the 1887 interview of Kreeta by Lilli Lilius, in his text he shed some light on points previously unmentioned.

An interest in Kreeta's life continues to the present day. Fortunately, in addition to the presentation given by Wirkkala and the booklet that followed, Kreeta Haapasalo's memoirs recorded by Lilli Lilius were published as well and the volume fills in many gaps. What is more, Heikki Laitinen supplemented the story and music of Kreeta Haapasalo in his 1990 book “An Icon and a Human Being” (Ikoni ja ihminen).

Then life follows its usual path: the young fall in love. When and how did it happen? The chaplain of Kaustinen Isak Hedberg's son Jaakko and Kreeta fell in love. A story tells that something came between them all of a sudden, and soon enough Joonas Virkkala, who already had a bride selected from his home village himself, switched ladies with the churchman's son. The switch satisfied both of them and the women did not protest, either. To be sure, there is no evidence of any conflict over the arrangement in the family since then.Ilmari Wirkkala wrote:”Kreeta's beautiful singing voice was already then well-known across the village, and the master said to her she shouldn't torture herself with sewing leather. She should just sing ‒ an easier and much more lucrative way of bringing food to the table.

Perhaps the parents were behind the arrangement, for in those days young people had little say in marriages. It seems that at least Kreeta's parents were pleased to accept the new addition to the family. This was likely because the Wirkkala house had seen many visitors of high stature, including great men such as dean and parliamentarian Antti Chydenius, returning there as a guest time after time.The house had previously served as the official residence of the local police chief and part of his responsibilities, according to Swedish law, had been to entertain all representatives of the king on official business. Following the establishment of inns this duty was no longer relevant, but despite this many high-profile visitors to the town followed the old tradition and still made their way to Vanhatalo where they were received as guests. Traditionally, it was the duty of the master of the house to drink up, to the health of his guests, the contents of a silver wine goblet that held two full bottles of wine. Presumably this led to the fact that the masters tended to be heavy drinkers – and their children sought to follow suit. Joonas's father Taneli was the eldest son in the house. Due to Taneli's inability to hold his liquor, however, his father Elias skipped him and left the house to his younger son Mikko. Taneli received his share in money and moved to the town of Toholampi where he built a house on a spot which was eventually to develop into the village of Wirkkala.

It was said of Taneli that he was a mean drunk. His daughter-in-law Liisa said as much when I met her in the village of Wirkkala in 1933. She was over 90 years of age at the time and originally from Lohtaja. Taneli and his family moved to Toholampi only in 1842; his son Joonas celebrated his marriage to Kreeta on midsummer's day in 1837.

Joonas was therefore representing the family as the son of the primary heir, but – highly controversially at the time – his own first child with Kreeta was born less than six months after the wedding, on 13th December 1837.

The young mother suffered greatly from the scorn directed at her by the community. It is a possibility that chaplain Hedberg's son was even accused to have fathered the child. Whatever the truth is, it remains unrecoverable to us after all these years.

My father, Juho Wirkkala (1855-1926), second cousin to the children of Joonas and Kreeta, possessed a wealth of knowledge of what went on in the family and he had a remarkable memory until his last days. He always skirted the matter of Joonas and Kreeta. As it were, Joonas was not allowed to bring his wife into his family home, but instead moved himself to her home in the village of Järvelä. The Wirkkala family of Vanhatalo pulled down the curtain and presumably forbade the family to ever raise the subject again.

Elias Wirkkala died in 1839 and Joonas's father left the town behind altogether in 1842.”

Ilmari's presentation on Kreeta Haapasalo and his writings on her ruffled some feathers which led to some unusual exchanges in the local press. Heikki Laitinen did not discuss this further in his book on Kreeta, and the same applied to biographer Lilli Lilius.

Ilmari subsequently used the rowan logotype on his envelopes, letterheads and brochures. Above the tree symbol stands a knight in armor, the symbolism of which likely relates to the family history and the story of croft soldier Juho Svartlock-Wirkkala.

The statue was created mainly at Tauno Wirkkala's home in Utti and transporting it to its final destination was no easy feat. When it was finally moved out, the atmosphere at Tauno Wirkkala's home studio calmed down and the family was able to get rid of the enormous figure smelling of clay. Tauno sculpted the front of the statue with its kantele out of clay and the figure was then cast in plaster. This quarter was then transported to a stone mason who finished the rest of the statue.

The statue was erected in Kaustinen, on the church hill, close to the old town hall and the bank building.

THE CHURCH IN TOHOLAMPI – TOHOLAMPI

Ilmari Wirkkala kept close contact with the neighboring parish of Toholampi already before the wars. In 1948-49, the stunning church in Toholampi was to be renovated thoroughly. Ilmari Wirkkala was tasked with the challenging mission to decorate the choir and the walls above the side doors with paintings.

On the sides of the choir he created delicate images of angels. One side had three angels in flight, one carrying a cross, the second a chalice and the third a plate with sacramental bread. The other side also came with three angels who were each holding a cross, a dove and a lit lamp. The right hand side had a plaque with the text: ”In memory of Doctoress Irja Koivikko. Gifted in 1949.”

On the walls of the organ loft, Wirkkala painted an angel playing the church organ. Above the door on the left, Wirkkala painted a figure of a man sowing seeds. The features were recognizably those of rector Lauri Kujanpää. The features of organist H.W. Pöyhtäri, in turn, can be found above the side door on the right where the piece shows a man reaping. Nowadays these works are covered by old paintings that Johan Backman created already in 1760. The angel playing the organ, in turn, has disappeared behind a set of modernized organ pipes.

At the choir, however, the angels remain visible. Due to the temperature changes inside the church, the angel paintings have needed conservation work every now and then.

The Toholampi parish also ordered new purple textiles for the altar from Selma Wirkkala. These still exist.

THE MONUMENT FOR THE WIRKKALA FAMILY – KAUSTINEN

After the wars, Ilmari Wirkkala traveled back to his home town several times and became increasingly interested in local heritage work and genealogy. During quieter periods in 1943, Ilmari began by arduously copying old maps which had been stored in the provincial archives since mid-1700s. O.V. Kankaanranta, born in Veteli, was a known genealogist who had engaged in a monumental effort to trace the families and individuals in the Perho river valley using a multitude of archives.

Kankaanranta knew that the effort had to be expanded to neighboring towns and he encouraged Ilmari Wirkkala to carry on his work. ”I didn't have the income of a bank manager needed to continue the work,” Ilmari wrote later in a published article, ”and so my efforts remained scattered attempts at pulling together information from various genealogists operating in nearby towns”.

“Everybody should have access to their own family tree through which to explore their past”, Ilmari Wirkkala wrote at the time. He began the monumental task of researching the Wirkkala family specifically, and finally finished the work in 1960. On 16th January 1960, he published his findings in a book form – a numbered edition of fabric-covered books containing ancestry charts and detailed family stories. The records prepared by Kankaanranta were of great help to him.

The book has since been examined by hundreds of members of the Wirkkala family. It is unfortunate that nobody in the family apart from Vilkko Virkkala has risen to the challenge of putting in the time and effort to continue Ilmari's work.

Ilmari kept a thank you letter sent by his good friend and fellow townsman from Kaustinen, Arvid Virkkala. Arvid had received Ilmari's book and he was clearly moved. “What a wonderful book. And what a gargantuan amount of work it must've required of you. A life's work”, Arvid wrote to Ilmari. “It felt as if I had arrived in a forest where there were no other paths than some anonymous ski tracks crisscrossing in the snow… I didn't know which way to go. But then the tracks started to grow more familiar. It was as if I was an explorer”, Arvid said of the book.

When researching the life of Kreeta Haapasalo, Ilmari had already dug deep into the family history passed down by his forefathers. Some of the charts of descendants had been completed towards the end of 1940s. The forefather of the Wirkkala family had been identified as Knut Kaustar who had moved from the shores of Kokkolanlahti in the Kaustari district of Kaarlela to the vicinity of the river Perho in Kaustinen.

It is, however, Knut Kaustar's son Matti Knutinpoika Wirkkala, that Ilmari considers to be the family's 'ancestor proper'. A village reeve, Matti owned a large one-mantal farm in the village of Wirkkala in 1549-1557. ”The oldest members of the family have traditionally been called 'officials' and the name of the manor itself derived from the Finnish word for official, 'virkamies' – Wirkala, Wirckala, Wirgala, eventually leading up to the current form Wirkkala”, Ilmari writes on the opening page of his genealogy work.

In the summer of 1949, 400 years had passed since 1549. To commemorate this, Ilmari Wirkkala along with some close family members set up the Wirkkala family association. He also designed a granite statue which was erected, in a grand family party at Vanhatalo, near a large rowan on the hill sloping down to the river. The tree had been transported there as a small sapling from behind a large rocky hill called Pööskallio and it had grown exceptionally large and strong. The tree was in beautiful bloom on that June day when the family gathering was held.

Members of the family donated money – one or two marks from here, five from there ‒ to fund the statue. Out of all the family members in the United States of America, Ilmari's half-brother Kalle (Charles) Wirkkala who lived in Naselle near the west coast of Washington state, had been particularly hard at work collecting donations. The American contributions, in dollars, were likewise recorded in the guest book at the family event.

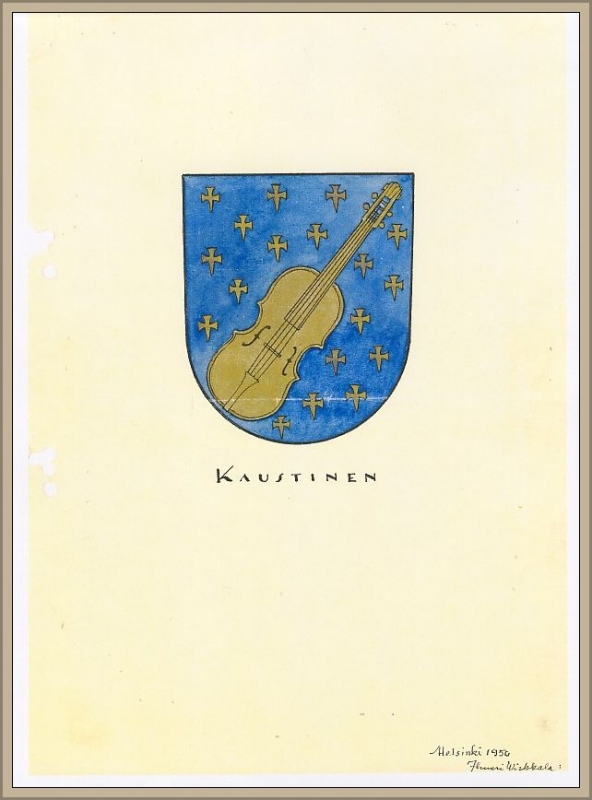

THE COAT OF ARMS OF KAUSTINEN – KAUSTINEN

When he turned 60 in 1950, Ilmari Wirkkala's creative energies were still flowing strong. He did not hesitate to explore new areas of art such as heraldry, and so he seized an opportunity to try and design a coat of arms for his home town Kaustinen.

The law of 1949 concerning coats of arms in Finland allowed not only cities but also municipalities to use a coat of arms. When the law was still being prepared, Kaustinen had already set up a commission consisting of three people to manage the acquisition of a coat of arms. Its chairwoman was Lyydia Järvelä.

The commission approached Ilmari Wirkkala and requested some sketches. They already had a suggestion as to its topic: a queen and her spinning wheel. This was related to the famous church building family of the Kuorikoskis. Church builder Antti Kuorikoski visited King Gustav III of Sweden in 1776, requesting permission to build a church in Kaustinen. As a gift, he presented to his spouse Queen Sophia Magdalena of Denmark a spinning wheel he had crafted.

In addition to the imagery of the queen and her spinning wheel, Ilmari Wirkkala also created two other designs. One of them came with a spinning wheel without a queen and the other one had the monument for the Kuorikoski family on it along with some ears of grain. The ears were there as a reminder of Kaustinen having already in 1918 been self-sufficient with regards to grain during the country’s worst period of scarcity. Indeed, the town was not only self-sufficient, it was even able to assist neighboring towns and go as far as to loan, with the help of the bank Säästöpankki, one million gold marks to the government with the aim of ultimately ending the Finnish Civil War. This is also why the ears were gilded. This last design was supported by the town council and it was subsequently sent on to the Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities in Helsinki for approval.

Helsinki did not, however, approve the gilded ears and Wirkkala proceeded to create a new sketch, this time depicting the wheel of a spinning wheel, a pair of compasses, a ruler and a silvery stream on a blue background. This did not get an approval either, apparently because it was too reminiscent of the Freemasons emblem.

In the next design the wheel of a spinning wheel, the pair of compasses and the ruler had changed into a golden kantele and a layout of a church. This design yielded yet another rejection from the capital, but Ilmari Wirkkala did not give up – he proceeded to present five new options.

Two new sketches had a kantele and a wheel of a spinning wheel, two came with a violin and one had a wheel of a spinning wheel together with some clover leaves. These and a few further designs did rounds at the Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, and all came back with annotations. The local commission in Kaustinen wanted to have a kantele on the coat of arms, but for some reason the association in Helsinki pushed back. As it turns out, the kantele was eventually changed into a violin.

The last three designs Ilmari Wirkkala completed in March 1950. In a letter to A. Vintturi he said: ”I've lost count of how many suggestions I have created, but other designers have surely done the same. This is not a game anymore.”

The sketches were sent out for approval once again and in the end they recommended a design which had a golden violin on a blue background, provided that it was amended to increase the number of cross fitchés. Wirkkala carried out the requested amendments and the end result only required a further approval from the local commission and the town council. The commission was not fully pleased with the design, but ended up approving it and dispatched it to the town council for final sign off.

Ilmari Wirkkala felt the need to defend his work and he wrote to the town council on 3rd of April 1950: ”The design promoted by the Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities shows – to me, as well as is possible – the overwhelming power of Kaustinen in all of the country in terms of the ratio between the number and quality of folk musicians. Kaustinen, in my opinion, rightfully should have the honor of having a violin in its coat of arms. I do not feel that even those who desired to have Jussi from Ylitalo depicted as a plowman on it instead, should protest. For he was also, in his day, a famous fiddler. I believe that the Kaustinen town council is open-minded enough to vote for the violin to be portrayed in its coat of arms. The instrument represents the town as the first and the oldest folk music town in the country.”

The council approved the coat of arms in its meeting on 21st of June 1950 and was among one of the first municipalities in Finland to do so. On 21st September that same year, the Ministry of the Interior confirmed the coat of arms and its official description: ”On blue field with scattered golden cross fitchés a bendwise sinister positioned golden violin.”

It is perhaps fair to presume that the artist interested in heraldry felt frustrated by the whole episode, just as he had been during the planning stages of his earlier war memorial work.

Despite this, Ilmari Wirkkala continued to work in heraldry. He corresponded with the towns of, for instance, Kälviä and Lestijärvi, offering them his designs. Kälviä, however, ended up going with a design by Gustaf von Numers, whose coat of arms was confirmed in 1962. Neighboring municipalities Veteli and Halsua also got their coats of arms, and for those, the kantele was approved. Thus the coat of arms for Kaustinen remains the only confirmed merit for Ilmari Wirkkala in the field of heraldry.